Yes, there are native foods on our national menu mostly seafood, such as prawns and barramundi. But the fact we eat relatively little kangaroo, emu, barramundi and crocodile – to name only the most popular bush animals – only illustrates how small a part native food plays in the typical Australian diet. Most Australians would struggle to name five native plants they've eaten.

With yet another drought biting deep into the productivity and profits of our farmers and sweltering summers becoming ever more frequent, this Australia Day is a good time to rethink what we farm and how we can develop our own native plants as crops.

But changing the tastes of Australia won't be easy.

Australia's climate can be harsh, drought prone and nutrient poor, particularly in broadacre cropping and pastoral districts. To get crops to grow in such regions requires selection and breeding for varieties that can tolerate, or better still, thrive in these conditions.

Crops originally from temperate regions, such as wheat and canola, have been extensively selected so that they can cope with warmer, dryer conditions. Crops from tropical or Mediterranean regions that are more climatically similar to Australia, like sugar cane, fare better with their innate adaptive capacity. But they are still prone to environmental extremes and local diseases.

While new plant varieties are continuously being developed the problem is that many of these species simply don't have the adaptive capacity to cope with the harshest Australian conditions.

Indigenous super foods

Over the past 50,000 years or so there has been some cultivation and selection of native food plants. But early settlers preferred familiar crops and largely ignored Australian plants. In establishing our primary production sector, we have fundamentally failed to harness the millennia of knowledge that exists of our native plants and animals, and have largely ignored the crop potential of the Australian biota.

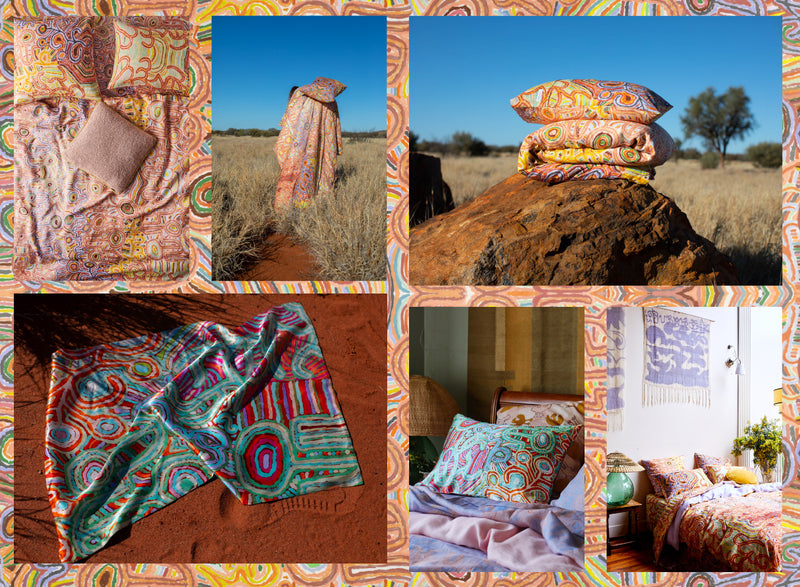

Of roughly 35,000 native plants here in Australia, some 1500 to 4500 have been used by Indigenous communities as food. There are a range of underutilised tubers, grains, nuts and fruits that could be developed as crops. Among the benefits of cultivating indigenous species is that many contain bioactive compounds that allow the plants to thrive in the extreme Australian environments and which have tremendous health benefits. For example, the Kakadu plum contains more than 100 times the vitamin C of oranges, and some native Australian Leptospermum species, commonly known as tea tree, have more than 10 times the antibacterial power of the New Zealand plants used to produce manuka honey.

There have been several attempts over the decades to develop a native food industry. Perhaps the only global success story is the macadamia nut, but the selection and breeding of this product was largely undertaken in Hawaii. Out of the world's top 150 crop plants, none come from Australia.

However, there exists a healthy cottage industry around native foods across much of the country and a number of agencies, including Australian Native Foods and Botanicals (ANFAB), research groups and communities have started to develop some of the 1500 or so edible plants.

Thirteen species have been prioritised: anise myrtle, bush tomato, Davidson plum, desert lime, finger limes, Kakadu plum, lemon aspen, lemon myrtle, muntries, mountain pepper, quandong, riberry and wattle seed. Apart from ice-creams made using some of these amazing flavours (e.g. in the Daintree), it is still difficult to buy these products. And until there is a degree of familiarity with the tastes, many would remain untouched on supermarket shelves even if they were to make their way there.

Chefs go native

Award-winning chef Jock Zonfrillo has taken up the native food mantle with gusto and his restaurant specialises in creating a delicious degustation from Australian native and local ingredients. Over the past decade, Zonfrillo has travelled around the country learning about native foods and their preparation from Indigenous communities. A typical evening's feast could include a starter of damper on lemon myrtle with smoked macadamia butter and native thyme; main course of Coorong mullet, lemon iron bark, Geraldton wax, native honey and green ants; and dessert of Northern Territory buffalo milk, strawberry and eucalyptus.

Jock has also established the Orana Foundation to help further develop the Australian native food industry. A key project of the foundation, which is supported by the South Australian government's Primary Industry and Regions SA departments, is to develop an indigenous food database, in partnership with the University of Adelaide, to help document and share knowledge about our native foods. The project will collate records of how foods are used and bring together information on the nutrient profile, culinary preparation and best horticultural practices for these products. The goal is to be a source of information about our delicious native foods – and to help cultivate and grow a discerning local and global customer base.

The complexity of preparing some native plants is a barrier to wide-scale use. Many are unpalatable and some can be poisonous if incorrectly handled. Millennia of experience passed down through generations of Indigenous Australians has identified how to overcome this by harvesting at the right moment and then using sophisticated preparation techniques, including washing for extended periods or cooking in water mixed with wood ash or charcoal, which binds to the toxins.

For the time being, chefs such as Paul Baker from the Botanic Gardens Restaurant in Adelaide are pioneering the use of native plants in dishes such as karkalla (a salty native succulent), miso butter, barilla bower spinach (endemic to Victoria) with barramundi, or samphire (similar to a salty asparagus) with quail eggs.

"I have developed a food calendar, to highlight when ingredients can be harvested and used," says Baker. "It helps me optimise my menu."

What's in a name?

If native foods are to become mainstream, we need to use them in our home cooking. Maggie Beer has already published a cook book that features native ingredients but it might also help if native foods had more appetising names. Many plants are known by their traditional or botanic origins. In some cases it is difficult to understand even what they are, never mind what you can do with them. For example, what you are supposed to do with Geraldton wax, pigface, youlk or quandong? The answers are: grind it and use it as a sauce; cook as a thick spinach; boil and serve as a root vegetable; eat as a fresh fruit or preserve as a jam.

For some species the terms "bush" or "desert" have been added to the name, which give clues to usage – e.g. bush tomato or desert plum. For others a description of their appearance or region of origin combined with a familiar fruit or vegetable name are helpful, such as Kakadu plum or finger limes.

Regardless of what they're called, if native plants are to become a consistent, secure and safe part of our diet we need to solve the problems of seasonality and low volumes. Several suppliers have taken up the challenge and have been building supply chains over time.

Something Wild provides a range of native game and fowl, along with a selection of fruit and vegetables. "We source 90 per cent of our products from Indigenous communities, most of it through government-permitted wild harvest," says managing director Daniel Motlop. "Our top products even featured on MasterChef, in a pop-up Something Wild Supermarket."

Buoyed by the success, Something Wild has branched out into other product lines. Last year it released Green Ant Gin, which was the result of a hugely successful collaboration with Adelaide Hills Distillery. "We are the only company in Australia that has a licence to wild-harvest green ants," Motlop says. "The high-end gin retails for around $100 and is highly prized by gin connoisseurs." The product has also featured in the most recent series of The Bachelorette, as part of a strategy to broaden its appeal.

Another collaboration, with the Fleurieu Milk Company, resulted in a Kakadu plum yoghurt. To smooth out supply issues and fix the price, an agreement was brokered by the Indigenous Land Corporation with 80 per cent of the Indigenous Kakadu plum producers and harvesters in Australia.

Selection and breeding

Developing a native food industry also provides an opportunity to support Indigenous communities and an opportunity to benefit from the millennia of knowledge surrounding native foods in these cultures. Many of the players in the market are Aboriginal-owned or operated, and some, like Something Wild, return a significant proportion of their sale price back to the Indigenous communities involved in wild harvest.

But here lies a fundamental issue for the industry: much native food is wild-harvested, but as interest builds, some form of enrichment planting or plantation will be required to keep pace with demand. That planting will need to be started now, if there isn't to be a major supply failure in the near future or an overharvesting of natural populations.

This path to major commercialisation could be a problem for the native food industry and its relationship with Indigenous communities that harvest foods from the wild. If the enrichment planting or plantations are established on traditional lands and the supply chain involves Indigenous communities, then the harvest could be done in a culturally appropriate way. Mass production without Indigenous involvement will break this link but may be required to bring the product to a global audience at a competitive price.

Another consideration is that almost all successful global crops have been through a range of intensive breeding and selection cycles. For wheat this process started 5000 years ago when the crop was first domesticated in the fertile crescent. The undomesticated banana, small and full of seeds, is almost unrecognisable from the product we eat today.

To improve the crop potential of native plants will require a real focus on selection and breeding. Traits such as production (e.g. growth, size), ease of harvest (size, shape and texture) and taste and texture characteristics (reduced bitterness and fibre) are essential characteristics to get right.

Amanda Garner, retiring chair of the Australian Native Food and Botanical Limited, says native crop development will require public and private investment.

But there is also an opportunity to develop a benefit-sharing framework which returns revenue back to Indigenous communities and native food research and development, from the profits made through new and improved varieties via plant breeders rights licensing agreements."

Such a system would see value returned to Aboriginal communities for the wide-scale commercialisation of selected Australian native plants. Ultimately native foods will need to be able to compete in a global market against more established crops and sophisticated marketing campaigns. But with an increasingly adventurous and burgeoning global middle class, keen for the next quinoa, there are opportunities. Indeed some Australian companies have started to penetrate global markets with native foods.

Macro meats, the largest seller of kangaroo and game meats overseas, has well-established markets in the US and Europe. Red Centre, which specialises in native food flavourings, has had success in China.

Christine Pitt, chief executive of the Food Futures Company and a director of Rocket Seeder, thinks that the appeal of native foods internationally is likely to be twofold.

"The first line for native foods must be to honour the traditions, story and Indigenous origin of native foods," she says. "While not necessarily only from wild-harvest, Australian native food produce which has cultural integrity, like kosher produce, has a unique global selling point. These markets are likely to be in Europe and liberal US states."

"The second global market for native foods is likely to be a more mass market, where large-scale production will be required to produce products at volume, and are produced for their health value. For example the high vitamin C and antioxidant qualities of Kakadu plum will sell well into such markets and large-scale plantations of this product will be needed to meet the anticipated demand. This demand is likely to come strongest from Asian countries, particularly China."

Article first published in The Australian Financial Review

Professor Andy Lowe is director of the Food Innovation Theme at the University of Adelaide, and is research lead of a native food research project with The Orana Foundation supported by the South Australian Government.